The Real Drug Lords Are Not Who You Think They Are

expand_moreThe CIA & drugs: https://thememoryhole.substack.com/p/the-cia-guide-to-ruining-someones

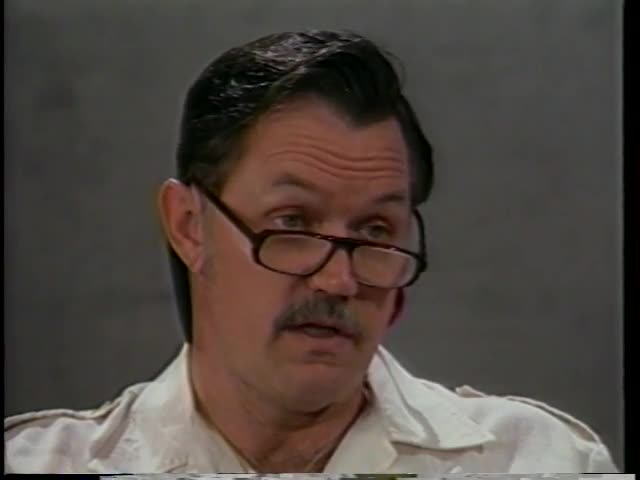

An in-depth exploration of the intricate web underlying the narcotics trade. Delivered by former CIA official John Stockwell, the presentation meticulously traces the evolution of this illicit business, beginning with the Opium Wars in China and extending through pivotal historical moments such as American support to Mafia and crime syndicates during and post-World War II.

Stockwell's narrative doesn't shy away from detailing the French narcotics involvement in Indo-China and the subsequent assumption of these operations by the United States during the Vietnam War. The presentation extends its gaze into the contemporary era, shedding light on how entities like the CIA and international banks play roles in fostering and profiting from the global narcotics trade.

A particular emphasis is placed on exploring the involvement of prominent figures like George Bush and Oliver North in these operations. Recorded on June 25, 1988, this comprehensive and thought-provoking exposition offers a deep dive into the history, structure, and operations of the narcotics trade, exposing connections and dynamics that span generations.

The Opium Wars (simplified Chinese: 鸦片战争; traditional Chinese: 鴉片戰爭 Yāpiàn zhànzhēng) were two conflicts waged between China and Western powers during the mid-19th century.

The First Opium War was fought from 1839 to 1842 between China and Britain. It was triggered by the Chinese government's campaign to enforce its prohibition of opium, which included destroying opium stocks owned by British merchants and the British East India Company. The British government responded by sending a naval expedition to force the Chinese government to pay reparations and allow the opium trade. [1] The Second Opium War was waged by Britain and France against China from 1856 to 1860. It resulted in the legalisation of opium in China. [2]

In each war, the superior military advantages enjoyed by European forces led to several easy victories over the Chinese military, with the consequence that China was compelled to sign the unequal treaties to grant favourable tariffs, trade concessions, reparations and territory to Western powers. The two conflicts, along with the various treaties imposed during the "century of humiliation", weakened the Chinese government's authority and forced China to open specified treaty ports (including Shanghai) to Western merchants.[3][4] In addition, China ceded sovereignty over Hong Kong to the British Empire, which maintained control over the region until 1997. During this period, the Chinese economy also contracted slightly as a result of the wars, though the Taiping Rebellion and Dungan Revolt had a much larger economic effect.[5]

First Opium War

Main article: First Opium War

The First Opium War broke out in 1839 between China and Britain and was fought over trading rights (including the right of free trade) and Britain's diplomatic status among Chinese officials. In the eighteenth century, China enjoyed a trade surplus with Europe, trading porcelain, silk, and tea in exchange for silver. By the late 17th century, the British East India Company (EIC) expanded the cultivation of opium in the Bengal Presidency, selling it to private merchants who transported it to China and covertly sold it on to Chinese smugglers.[6] By 1797, the EIC was selling 4,000 chests of opium (each weighing 77 kg) to private merchants per annum.[7]

In earlier centuries, opium was utilised as an medicine with anesthetic qualities, but new Chinese practices of smoking opium recreationally increased demand tremendously and often led to smokers developing addictions. Successive Chinese emperors issued edicts making opium illegal in 1729, 1799, 1814, and 1831, but imports grew as smugglers and colluding officials in China sought profit.[8] Some American merchants entered the trade by smuggling opium from Turkey into China, including Warren Delano Jr., the grandfather of twentieth-century President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Francis Blackwell Forbes; in American historiography this is sometimes referred to as the Old China Trade.[9] By 1833, the Chinese opium trade soared to 30,000 chests.[7] British and American merchants sent opium to warehouses in the free-trade port of Canton, and sold it to Chinese smugglers.[8][10]

In 1834, the EIC's monopoly on British trade with China ceased, and the opium trade burgeoned. Partly concerned with moral issues over the consumption of opium and partly with the outflow of silver, the Daoguang Emperor charged Governor General Lin Zexu with ending the trade. In 1839, Lin published in Canton an open letter to Queen Victoria requesting her cooperation in halting the opium trade. The letter never reached the Queen.[11] It was later published in The Times as a direct appeal to the British public for their cooperation.[12] An edict from the Daoguang Emperor followed on 18 March,[13] emphasising the serious penalties for opium smuggling that would now apply henceforth. Lin ordered the seizure of all opium in Canton, including that held by foreign governments and trading companies (called factories),[14] and the companies prepared to hand over a token amount to placate him.[15][page needed] Charles Elliot, Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China, arrived 3 days after the expiry of Lin's deadline, as Chinese troops enforced a shutdown and blockade of the factories. The standoff ended after Elliot paid for all the opium on credit from the British government (despite lacking official authority to make the purchase) and handed the 20,000 chests (1,300 metric tons) over to Lin, who had them destroyed at Humen.[16]

Elliott then wrote to London advising the use of military force to resolve the dispute with the Chinese government. A small skirmish occurred between British and Chinese warships in the Kowloon Estuary on 4 September 1839.[14] After almost a year, the British government decided, in May 1840, to send a military expedition to impose reparations for the financial losses experienced by opium traders in Canton and to guarantee future security for the trade. On 21 June 1840, a British naval force arrived off Macao and moved to bombard the port of Dinghai. In the ensuing conflict, the Royal Navy used its superior ships and guns to inflict a series of decisive defeats on Chinese forces.[17]

The war was concluded by the Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing) in 1842, the first of the Unequal treaties between China and Western powers.[18] The treaty ceded the Hong Kong Island and surrounding smaller islands to Britain, and established five cities as treaty ports open to Western traders: Shanghai, Canton, Ningbo, Fuzhou, and Xiamen (Amoy).[19] The treaty also stipulated that China would pay a twenty-one million dollar payment to Britain as reparations for the destroyed opium, with six million to be paid immediately, and the rest through specified installments thereafter.[20] Another treaty the following year gave most favoured nation status to Britain and added provisions for British extraterritoriality, making Britain exempt from Chinese law.[18] France secured several of the same concessions from China in the Treaty of Whampoa in 1844.[21]

British bombardment of Canton from the surrounding heights, 29 May 1841. Watercolour painting by Edward H. Cree (1814–1901), Naval Surgeon to the Royal Navy.

British bombardment of Canton from the surrounding heights, 29 May 1841. Watercolour painting by Edward H. Cree (1814–1901), Naval Surgeon to the Royal Navy.

The 98th Regiment of Foot at the attack on Chin-Kiang-Foo (Zhenjiang), 21 July 1842, resulting in the defeat of the Manchu government. Watercolour by military illustrator Richard Simkin (1840–1926).

The 98th Regiment of Foot at the attack on Chin-Kiang-Foo (Zhenjiang), 21 July 1842, resulting in the defeat of the Manchu government. Watercolour by military illustrator Richard Simkin (1840–1926).

Second Opium War

Main article: Second Opium War

Depiction of the 1860 battle of Taku Forts. Book illustration from 1873.

In 1853, northern China was convulsed by the Taiping Rebellion, which established its capital at Nanjing. In spite of this, a new Imperial Commissioner, Ye Mingchen, was appointed at Canton, determined to stamp out the opium trade, which was still technically illegal. In October 1856, he seized the Arrow, a ship claiming British registration, and threw its crew into chains. Sir John Bowring, Governor of British Hong Kong, called up Rear Admiral Sir Michael Seymour's East Indies and China Station fleet, which, on 23 October, bombarded and captured the Pearl River forts on the approach to Canton and proceeded to bombard Canton itself, but had insufficient forces to take and hold the city. On 15 December, during a riot in Canton, European commercial properties were set on fire and Bowring appealed for military intervention.[19] The execution of a French missionary inspired support from France.[22]

Britain and France now sought greater concessions from China, including the legalisation of the opium trade, expanding of the transportation of coolies to European colonies, opening all of China to British and French citizens and exempting foreign imports from internal transit duties.[23] The war resulted in the 1858 Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin), in which the Chinese government agreed to pay war reparations for the expenses of the recent conflict, open a second group of ten ports to European commerce, legalise the opium trade, and grant foreign traders and missionaries rights to travel within China.[19] After a second phase of fighting which included the sack of the Old Summer Palace and the occupation of the Forbidden City palace complex in Beijing, the treaty was confirmed by the Convention of Peking in 1860.[citation needed]

See also

Destruction of opium at Humen

History of opium in China

References

Chen, Song-Chuan (1 May 2017). Merchants of War and Peace. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8390-56-4.

Feige1, Miron2, Chris1, Jeffrey A.2 (2008). "The opium wars, opium legalization and opium consumption in China". Applied Economics Letters. 15: 911–913 – via Scopus.

Taylor Wallbank; Bailkey; Jewsbury; Lewis; Hackett (1992). "A Short History of the Opium Wars". Civilizations Past And Present. Chapter 29: "South And East Asia, 1815–1914" – via Schaffer Library of Drug Policy.

Kenneth Pletcher. "Chinese history: Opium Wars". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Desjardins, Jeff (15 September 2017). "Over 2000 years of economic history, in one chart". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

"Opium trade – History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

Hanes, Wiliam Travis III; Sanello, Frank (2004). The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. United States: Sourcebooks. pp. 21, 24, 25. ISBN 978-1402201493.

"A Century of International Drug Control" (PDF). UNODC.org.

Meyer, Karl E. (28 June 1997). "The Opium War's Secret History". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

Haythornthwaite, Philip J., The Colonial Wars Source Book, London, 2000, p.237. ISBN 1-84067-231-5

Fay (1975), p. 143.

Platt (2018), p. online.

Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 43.

Haythornthwaite, 2000, p.237.

Hanes, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2002). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. ISBN 9781402201493.

"China Commemorates Anti-opium Hero". 4 June 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

Tsang, Steve (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I. B. Tauris. pp. 3–13, 29. ISBN 1-84511-419-1.

Treaty of Nanjing inBritannica.

Haythornthwaite 2000, p. 239.

Treaty Of Nanjing (Nanking), 1842 on the website of the US-China Institute at University of Southern Carolina.

Xiaobing Li (2012). China at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 468. ISBN 9781598844160.

"MIT Visualizing Cultures". visualizingcultures.mit.edu. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

Zhihong Shi (2016). Central Government Silver Treasury: Revenue, Expenditure and Inventory Statistics, ca. 1667–1899. BRILL. p. 33. ISBN 978-90-04-30733-9.

Cited references and further reading

Beeching, Jack. The Chinese Opium Wars (Harvest Books, 1975)

Fay, Peter Ward (1975). The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the War by Which They Forced Her Gates Ajar. University of North Carolina Press.

Gelber, Harry G. Opium, Soldiers and Evangelicals: Britain's 1840–42 War with China, and its Aftermath. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Hanes, W. Travis and Frank Sanello. The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another (2014)

Kitson, Peter J. "The Last War of the Romantics: De Quincey, Macaulay, the First Chinese Opium War". Wordsworth Circle (2018) 49#3.

Lovell, Julia. The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of Modern China(2011).

Marchant, Leslie R. "The War of the Poppies", History Today (May 2002) Vol. 52 Issue 5, pp 42–49, online popular history

Platt, Stephen R. (2018). Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780307961730. 556 pp.

Kenneth Pomeranz, "Blundering into War" (review of Stephen R. Platt, Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age, Vintage), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 10 (6 June 2019), pp. 38–41.

Polachek, James M., The inner opium war (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1992).

Wakeman, Frederic E. (1966). Strangers at the Gate: Social Disorder in South China, 1839–1861. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520212398.

Waley, Arthur, ed. The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes (1960).

Wong, John Y. Deadly Dreams: Opium, Imperialism, and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China. (Cambridge UP, 2002)

Yu, Miles Maochun. "Did China Have a Chance to Win the Opium War?" Military History in the News, July 3, 2018.

The United States government collaborated with the Italian Mafia during World War II and afterwards on several occasions.

Operation Underworld: Strikes and labor disputes in the eastern shipping ports

See also: Operation Underworld

During the early days of World War II, the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence suspected that Italian and German agents were entering the United States through New York, and that these facilities were susceptible to sabotage. The loss of SS Normandie in February 1942, especially, raised fears and suspicions in the Navy about possible sabotage in the Eastern ports. A Navy Intelligence Unit, B3, assigned more than a hundred agents to investigate possible Benito Mussolini supporters within the predominantly Italian-American fisherman and dockworker population on the waterfront. Their efforts were fruitless, as the dockworkers and fishermen in the Italian Mafia-controlled waterfront were tight-lipped and distant to strangers.[1] The Navy contacted Meyer Lansky, a known associate of Salvatore C. Luciano and one of the top non-Italian associates of the Mafia,[2] about a deal with the Mafia boss Luciano. Luciano, also known as Lucky Luciano, was one of the highest-ranking Mafia both in Italy and the US and was serving a 30 to 50 years sentence for compulsory prostitution in the Clinton Prison.[3] To facilitate the negotiations, the State of New York moved Luciano from the Clinton prison to Great Meadow Correctional Facility, which is much closer to New York City.[4][5]

The State of New York, Luciano and the Navy struck a deal in which Luciano guaranteed full assistance of his organization in providing intelligence to the Navy. In addition, Luciano associate Albert Anastasia—who controlled the docks and ran Murder, Inc.—allegedly guaranteed no dockworker strikes throughout the war. In return, the State of New York agreed to commute Luciano's sentence.[6] Luciano's actual influence is uncertain, but the authorities did note that the dockworker strikes stopped after the deal was reached with Luciano.[7]

In the summer of 1945, Luciano petitioned the State of New York for executive clemency, citing his assistance to the Navy. Naval authorities, embarrassed that they had to recruit organized-crime to help in their war effort, declined to confirm Luciano's claim. However, the Manhattan District Attorney's office validated the facts and the state parole board unanimously agreed to recommend to the governor that Luciano be released and deported immediately.[8] On January 4, 1946, Governor Thomas E. Dewey, the former prosecutor who placed Luciano into prison, commuted Lucky Luciano's sentence on the condition that he did not resist deportation to Italy.[9] Dewey stated, “Upon the entry of the United States into the war, Luciano’s aid was sought by the Armed Services in inducing others to provide information concerning possible enemy attack. It appears that he cooperated in such effort, although the actual value of the information procured is not clear.”[10][7] Luciano was deported to his homeland Italy on February 9, 1946.[11] There was a media hype of Luciano's role after his deportation. The syndicated columnist and radio broadcaster Walter Winchell even reported in 1947 that Luciano would receive the Medal of Honor for his secret services.[12]

Operation Husky: The invasion of Sicily and its aftermath

See also: Allied invasion of Sicily

Italian Americans were very helpful in the planning and execution of the invasion of Sicily. The Mafia was involved in assisting the U.S. war efforts.[13] Luciano's associates found numerous Sicilians to help the Naval Intelligence draw maps of the harbors of Sicily and dig up old snapshots of the coastline.[14][15] Vito Genovese, another Mafia boss, offered his services to the U.S. Army and became an interpreter and advisor to the U.S. Army military government in Naples. He quickly became one of AMGOT’s most trusted employees.[16] Through the Navy Intelligence’s Mafia contacts from Operation Underworld, the names of Sicilian underworld personalities and friendly Sicilian natives who could be trusted were obtained and actually used in the Sicilian campaign.[17]

The Joint Staff Planners (JSP) for the US Joint Chiefs of Staff drafted a report titled Special Military Plan for Psychological Warfare in Sicily that recommended the “Establishment of contact and communications with the leaders of separatist nuclei, disaffected workers, and clandestine radical groups, e.g., the Mafia, and giving them every possible aid.” The report was approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington on April 15, 1943.[18]

Assassination attempts on Fidel Castro

Main article: Assassination attempts on Fidel Castro

See also: Sam Giancana and Santo Trafficante Jr.

[icon]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2018)

Controversy and criticism

There was considerable public controversy during the late days of the war and afterwards surrounding the connection between the U.S. Government and the Mafia.[19][20] In 1953, Governor Dewey, pushed by allegations that he sold Luciano his pardon, ordered a confidential investigation by the state's commissioner of investigation, William Herlands. Herlands released his 2,600-page report in 1954, which offered proof of Luciano's involvement with the Navy without finding any wrongdoing by Dewey.[21] Naval officials reviewed the report and requested Dewey to not release it on the grounds that it would be a public-relations disaster for the Navy and it might damage future similar war efforts. Dewey agreed, and the report was not released until after his death in the mid-1970s.[20][22]

Notable scholars of the topic such as Selwyn Raab and Tim Newark have questioned the effectiveness of the Mafia in their help during Operation Husky.[23][24] Raab states that Luciano could not have helped during the invasion of Sicily, as he was out of touch with the Sicilian Mafia, and neither he nor the Cosa Nostra had any significant contribution to the Allied victory in Sicily. On the other hand, another scholar on the topic, Ezio Costanzo, alleges that Congressman Horan revealed that Luciano was visited 11 times by Naval Intelligence officers throughout his sentence.[25] In addition, Costanzo states that Commander Haffenden of Naval Intelligence Section F (foreign intelligence) stated in numerous reports how his men were interviewing many native-born Italians and that they were cooperating because of Luciano.[26]

Footnotes

Raab. p.76

U.S. Treasury Department Bureau of Narcotics. p. 101

U.S. Treasury Department Bureau of Narcotics. p. 809

Kelly. p. 107

Costanzo. pp.51-56

Newark. pp. 99-111

Campbell. pp. 111-127

Raab. p. 78

"DEWEY COMMUTES LUCIANO SENTENCE,", The New York Times, 04 January 1946, Retrieved 25 March 2013

Costanzo. p.42

Costanzo. p.41

Raab. pp.78-79

Luconi. p.5

Raab. p.77

Newark. p.127

McCoy. p. 20

Newark. p.126

Newark. p.134-135

Costanzo. p.64

Raab. p.79

Costanzo. p.66

Costanzo. p.40

Costanzo. p.77

Newark. pp.288-289

Costanzo. p.44

Costanzo. p.59

References

Campbell, Rodney. The Luciano Project: The Secret Wartime Collaboration of the Mafia and the U.S. Navy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977. ISBN 9780070096745

Costanzo, Ezio. The Mafia and the Allies: Sicily 1943 and the Return of the Mafia. New York: Enigma Books, 2007. ISBN 9781936274949

Costanzo, Ezio. Mafia & Alleati, Servizi segreti americani e sbarco in Sicilia. Da Lucky Luciano ai sindaci uomini d'onore. Le Nove Muse Editrice, 2006

Kelly, Robert. The Upperworld and the Underworld: Case Studies of Racketeering and Business Infiltrations in the United States. New York: Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers, 1999.

Luconi, Stefano. "Italian Americans and the Invasion of Sicily in World War II." Italian Americana 25.1 (2007): 5-22.

McCoy, Alfred W. The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. New York: Harper and Row, 1972.

New York Times. "DEWEY COMMUTES LUCIANO SENTENCE." 4 January 1946. New York Times. 25 March 2013.

Newark, Tim. Mafia Allies: The True Story of America's Secret Alliance with the Mob in World War II. Saint Paul: Zenith Press, 2007, ISBN 9780760324578.

Raab, Selwyn. Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Mast Powerful Mafia Empires. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2005, ISBN 9780312300944

U.S. Treasury Department Bureau of Narcotics. Mafia. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007.

The French Connection was a scheme through which heroin was smuggled from Indochina through Turkey to France and then to the United States and Canada. The operation started in the 1930s, reached its peak in the 1960s, and was dismantled in the 1970s. It was responsible for providing the vast majority of the heroin used in the United States at the time. The operation was headed by Corsicans Antoine Guérini and Paul Carbone (with associate François Spirito). It also involved Auguste Ricord, Paul Mondoloni and Salvatore Greco.[citation needed]

History

The 1930s, '40s, and '50s

Illegal heroin labs were first discovered near Marseille, France, in 1937. These labs were run by Corsican gang leader Paul Carbone. For years, the Corsican underworld had been involved in the manufacturing and trafficking of heroin, primarily to the United States.[1] It was this heroin network that eventually became known as "the French Connection".

The Corsican Gang was protected by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the SDECE after World War II in exchange for working to prevent French Communists from bringing the Old Port of Marseille under their control.[2]

Historically, the raw material for most of the heroin consumed in the United States came from Indochina, then Turkey. Turkish farmers were licensed to grow opium poppies for sale to legal drug companies, but many sold their excess to the underworld market, where it was manufactured into heroin and transported to the United States. The morphine paste was refined in Corsican laboratories in Marseille, one of the busiest ports in the western Mediterranean Sea, known for shipping all types of illegal goods. The Marseille heroin was considered high quality.

The convenience of the port at Marseille and the frequent arrival of ships from opium-producing countries made it easy to smuggle the morphine base to Marseille from the Far East or the Near East. The French underground would then ship large quantities of heroin from Marseille to New York City.

The first significant post-World War II seizure was made in New York on February 5, 1947, when seven pounds (3 kg) of heroin were seized from a Corsican sailor disembarking from a vessel that had just arrived from France.

It soon became clear that the French underground was increasing not only its participation in the illegal trade of opium, but also its expertise and efficiency in heroin trafficking. On March 17, 1947, 28 pounds (13 kg) of heroin were found on the French liner St. Tropez. On January 7, 1949, more than 50 pounds (22.75 kg) of opium and heroin were seized on the French ship Batista.

After Paul Carbone's death, the Guérini clan was the ruling dynasty of the Unione Corse and had systematically organized the smuggling of opium from Turkey and other Middle Eastern countries. The Guérini clan was led by Marseille mob boss Antoine Guérini and his brothers, Barthelemy, Francois and Pascal.[citation needed]

In October 1957, a meeting between Sicilian Mafia and American Mafia members was held at the Grand Hotel et des Palmes in Palermo to discuss the international illegal heroin trade in the French Connection.[3]

The 1960s

The first major French Connection seizure in the 1960s began that June, when an informant told a drug agent in Lebanon that Mauricio Rosal, the Guatemalan Ambassador to Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, was smuggling morphine base from Beirut to Marseille. Narcotics agents had been seizing about 200 pounds (90 kg) of heroin in a typical year, but intelligence showed that the Corsican traffickers were smuggling in 200 pounds (90 kg) every other week. Rosal alone, in one year, had used his diplomatic status to bring in about 440 pounds (200 kg).

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics's 1960 annual report estimated that from 2,600 to 5,000 pounds (1,200 to 2,300 kg) of heroin were coming into the United States annually from France. The French traffickers continued to exploit the demand for their illegal product, and by 1969, they were supplying the United States with 80 percent of its heroin.[4]

On April 26, 1968, a record setting seizure was made, 246 lb (111.6 kg) of heroin smuggled to New York concealed in a Citroën DS on the SS France (1960) ocean liner.[5][6][7] The total amount smuggled during the many transatlantic voyages of just this one car was 1,606 lb (728.5 kg) according to arrested smuggler Jacques Bousquet.[8]

In an effort to limit the most proximate source of supply to the Corsican cartel, US officials went to Turkey to negotiate the phasing out of opium production. Initially, the Turkish government agreed to limit their opium production starting with the 1968 crop.

At the end of the 1960s, after Robert Blemant's assassination by Antoine Guérini, a gang war sparked in Marseille, caused by competition over casino revenues. Blemant's associate Marcel Francisci continued the war over the next years.

Jean Jehan

Former New York City Police Department Narcotics Bureau detective Sonny Grosso has stated that the kingpin of the French Connection heroin ring during the 1950s into the 1960s was Corsican Jean Jehan.[9] Although Jehan is reported to have arranged the famous 1962 deal gone wrong of 64 pounds of "pure" heroin, he was never arrested for his involvement in international heroin smuggling. According to Grosso, all warrants for the arrest of Jehan were left open. For years thereafter, Jehan was reported to be seen arranging and operating drug activities at will throughout Europe. According to William Friedkin, director of the 1971 film The French Connection, Jehan had been a member of the French Resistance to Nazi Occupation during World War II and, because of that, French law enforcement officials refused to arrest him. Friedkin was told that Jehan died peacefully of old age at his home in Corsica.[10]

The 1970s: Dismantling

Following five subsequent years of concessions, combined with international cooperation, the Turkish government finally agreed in 1971 to a complete ban on the growing of Turkish poppies for the production of opium, effective June 29, 1971. During these protracted negotiations, law enforcement personnel went into action. One of the major roundups began on January 4, 1972, when agents from the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) and French authorities seized 110 pounds (50 kg) of heroin at the Paris airport. Subsequently, traffickers Jean-Baptiste Croce and Joseph Mari were arrested in Marseille. One such French seizure from the French Connection in 1973 netted 210 pounds (95 kg) of heroin worth $38 million.

In February 1972, French traffickers offered a United States Army sergeant $96,000 (equivalent to $671,618 in 2022) to smuggle 240 pounds (109 kg) of heroin into the United States. He informed his superior who in turn notified the BNDD. As a result of this investigation, five men in New York and two in Paris were arrested with 264 pounds (120 kg) of heroin, which had a street value of $50 million. In a 14-month period, starting in February 1972, six major illicit heroin laboratories were seized and dismantled in the suburbs of Marseille by French national narcotics police in collaboration with agents from the United States Drug Enforcement Administration. On February 29, 1972, French authorities seized the shrimp boat, Caprice des Temps, as it put to sea near Marseille heading towards Miami. It was carrying 915 pounds (415 kg) of heroin. Drug arrests in France skyrocketed from 57 in 1970 to 3,016 in 1972.

Also broken up as part of this investigation was the crew of American Mafia Lucchese family mobster Vincent Papa, whose members included Anthony Loria Sr. and Virgil Alessi. The well-organized gang was responsible for distributing close to a million dollars worth of heroin up and down the East Coast of the United States during the early 1970s, which in turn led to a major New York Police Department (NYPD) corruption scheme. The scope and depth of this scheme are still not known, but officials suspect it involved corrupt NYPD officers who allowed Papa, Alessi, and Loria access to the NYPD property/evidence storage room, where hundreds of kilograms of heroin lay seized from the now-infamous French Connection bust, and from which the men would help themselves and replace missing heroin with flour and corn starch to avoid detection.[11][12]

The substitution was discovered only when officers noticed insects eating all the bags of "heroin". By that point an estimated street value of approximately $70 million worth of heroin had already been taken. The racket was brought to light and arrests were made. Certain plotters received jail sentences, including Papa, who was later murdered in federal prison in Atlanta, Georgia.

Ultimately, the Guérini clan was exterminated during internecine wars within the French underworld. In 1971, Marcel Francisci was accused by the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics of being involved in the trafficking of heroin between Marseilles and New York City.[13] On 16 January 1982, Marcel Francisci was shot to death as he was entering his car in the parking lot of the building where he lived in Paris, France.[13]

List of related gangsters

Unione Corse members

Paul Carbone

Marcel Francisci

Antoine Guérini

Barthélemy Guérini

Paul Mondoloni

Joseph Corsini

Francois Spirito

Black members

Frank Matthews

Italian-Canadian mobsters

Johnny Papalia, Hamilton, Ontario

Vito Agueci, Hamilton

Alberto Agueci, Hamilton

Vic Cotroni, leader of the Cotroni crime family of Montreal and capo/boss of the Montreal faction of the Bonanno crime family

Italian-American mobsters

Ignacio Antinori, Tampa, Florida gangster that founded Trafficante crime family

Frank Caruso[14]

Lucky Luciano, Five Families gangster that founded Genovese crime family

Vinnie Mauro[14]

Frank Ragano, Tampa, Florida attorney supporting Trafficante crime family

Joseph "Hoboken Joe" Stassi (AKA "Joe Rogers"), independent but well-placed in organized crime[15][16]

Bonanno crime family members

Joseph Bonanno, Bonanno crime family boss

Carmine Galante

Gambino crime family members

Joseph Armone[17]

Lucchese crime family members

Giovanni "Big John" Ormento, a capo involved in large scale narcotic trafficking[18]

Salvatore Lo Proto, an important member of Big John's narcotic trafficking ring[19]

Angelo M. Loiacano, wholesaler of Big John Ormento's narcotic trafficking ring[20]

Angelo "Little Angie" Tuminaro, an associate, involved in narcotic trafficking[18][21]

Pasquale "Patsy" Fuca, nephew to Tuminaro, involved in the narcotic trade[18]

Anthony DiPasqua, was a narcotic trafficker[18]

Vincent Papa, was the mastermind behind the "Stealing of the French Connection"

Anthony Loria, partner with Vincent Papa in the "Stealing of the French Connection"

Related films

William Friedkin, The French Connection (1971)

Francis Ford Coppola, The Godfather (1972)

Sidney J. Furie, Hit! (1973)

Robert Parrish, The Marseille Contract (1974)

John Frankenheimer, French Connection II (1975)

Andrew V. McLaglen, Mitchell (1975)

Blake Edwards, Revenge of the Pink Panther (1978)

Sidney Lumet, Prince of the City (1981)

Ridley Scott, American Gangster (2007)

Cédric Jimenez, The Connection (La French) (2014)

During the Korean War, the first allegations of CIA drug trafficking surfaced after 1949, stemming from a deal whereby arms were supplied to Chiang Kai-shek's defeated generals in exchange for intelligence.[15] Later in the same region, while the CIA was sponsoring a "Secret War" in Laos from 1961 to 1975, it was openly accused of trafficking heroin in the Golden Triangle area.

To fight its "Secret War" against the Pathet Lao communist movement of Laos, the CIA used the Miao/Meo (Hmong) population. Because of the war, the Hmong depended upon opium poppy cultivation for hard currency. The Plain of Jars had been captured by Pathet Lao fighters in 1964, which resulted in the Royal Lao Air Force being unable to land its C-47 transport aircraft on the Plain of Jars for opium transport. The Royal Laotian Air Force had almost no light planes that could land on the dirt runways near the mountaintop poppy fields. Having no way to transport their opium, the Hmong were faced with economic ruin. Air America, a CIA front organization, was the only airline available in northern Laos. Alfred McCoy writes, "According to several unproven sources, Air America began flying opium from mountain villages north and east of the Plain of Jars to CIA asset Hmong General Vang Pao's headquarters at Long Tieng."[16]

The CIA's front company, Air America was alleged to have profited from transporting opium and heroin on behalf of Hmong leader Vang Pao,[17][18] or of "turning a blind eye" to the Laotian military doing it.[19][20] This allegation has been supported also by former Laos CIA paramilitary Anthony Poshepny (aka Tony Poe), former Air America pilots, and other people involved in the war. It is portrayed in the movie Air America. Larry Collins alleged:

During the Vietnam War, US operations in Laos were largely a CIA responsibility. The CIA's surrogate there was a Laotian general, Vang Pao, who commanded Military Region 2 in northern Laos. He enlisted 30,000 Hmong tribesmen in the service of the CIA. These tribesmen continued to grow, as they had for generations, the opium poppy. Before long, someone—there were unproven allegations that it was a Mafia family from Florida—had established a heroin drug refinery lab in Region Two. The lab's production was soon being ferried out on the planes of the CIA's front airline, Air America. A pair of BNDD [the predecessor of the US Drug Enforcement Administration] agents tried to seize an Air America."[15]

Further documentation of CIA-connected Laotian opium trade was provided by Rolling Stone magazine in 1968, and by Alfred McCoy in 1972.[21][17] McCoy stated that:

In most cases, the CIA's role involved various forms of complicity, tolerance or studied ignorance about the trade, not any direct culpability in the actual trafficking ... [t]he CIA did not handle heroin, but it did provide its drug lord allies with transport, arms, and political protection. In sum, the CIA's role in the Southeast Asian heroin trade involved indirect complicity rather than direct culpability.[22]

However, aviation historian William M. Leary, writes that Air America was not involved in the drug trade, citing Joseph Westermeyer, a physician and public health worker resident in Laos from 1965 to 1975, that "American-owned airlines never knowingly transported opium in or out of Laos, nor did their American pilots ever profit from its transport."[23] Aviation historian Curtis Peebles also denies that Air America employees were involved in opium transportation.[24]

The dark side of history: https://thememoryhole.substack.com/

In espionage parlance, a cutout is a mutually trusted intermediary, method or channel of communication that facilitates the exchange of information between agents. Cutouts usually know only the source and destination of the information to be transmitted, not the identities of any other persons involved in the espionage process (need to know basis). Thus, a captured cutout cannot be used to identify members of an espionage cell. The cutout also isolates the source from the destination, so neither necessarily knows the other.

Outside espionage

Some computer protocols, like Tor, use the equivalent of cutout nodes in their communications networks. The use of multiple layers of encryption usually stops nodes on such networks from knowing the ultimate sender or receiver of the data.

In computer networking, darknets have some cutout functionality. Darknets are distinct from other distributed peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, as sharing is anonymous, i.e., IP addresses are not publicly shared and nodes often forward traffic to other nodes. Thus, with a darknet, users can communicate with little fear of governmental or corporate interference.[1] Darknets are thus often associated with dissident political communications as well as various illegal activities.

A dead drop or dead letter box is a method of espionage tradecraft used to pass items or information between two individuals (e.g., a case officer and an agent, or two agents) using a secret location. By avoiding direct meetings, individuals can maintain operational security. This method stands in contrast to the live drop, so-called because two persons meet to exchange items or information.

Spies and their handlers have been known to perform dead drops using various techniques to hide items (such as money, secrets or instructions) and to signal that the drop has been made. Although the signal and location by necessity must be agreed upon in advance, the signal may or may not be located close to the dead drop itself. The operatives may not necessarily know one another or ever meet.[1][2]

Considerations

The location and nature of the dead drop must enable retrieval of the hidden item without the operatives being spotted by a member of the public, the police, or other security forces—therefore, common everyday items and behavior are used to avoid arousing suspicion. Any hidden location could serve, although often a cut-out device is used, such as a loose brick in a wall, a (cut-out) library book, or a hole in a tree.

Dead drop spike

A dead drop spike is a concealment device similar to a microcache. It has been used since the late 1960s to hide money, maps, documents, microfilm, and other items. The spike is water- and mildew-proof and can be pushed into the ground or placed in a shallow stream to be retrieved at a later time.

Signaling devices can include a chalk mark on a wall, a piece of chewing gum on a lamppost, or a newspaper left on a park bench. Alternatively, the signal can be made from inside the agent's own home, by, for example, hanging a distinctively-colored towel from a balcony, or placing a potted plant on a window sill where it is visible to anyone on the street.

Drawbacks

While the dead drop method is useful in preventing the instantaneous capture of either an operative/handler pair or an entire espionage network, it is not without disadvantages. If one of the operatives is compromised, they may reveal the location and signal for that specific dead drop. Counterintelligence can then use the dead drop as a double agent for a variety of purposes, such as to feed misinformation to the enemy or to identify other operatives using it or ultimately to booby trap it.[3] There is also the risk that a third party may find the material deposited.

Modern techniques

See also: Short-range agent communications

On January 23, 2006, the Russian FSB accused Britain of using wireless dead drops concealed inside hollowed-out rocks ("spy rock") to collect espionage information from agents in Russia. According to the Russian authorities, the agent delivering information would approach the rock and transmit data wirelessly into it from a hand-held device, and later, his British handlers would pick up the stored data by similar means.[4]

SecureDrop, initially called DeadDrop, is a software suite for teams that allows them to create a digital dead drop location to receive tips from whistleblowers through the Internet. The team members and whistleblowers never communicate directly and never know each other's identity, therefore allowing whistleblowers to dead-drop information despite the mass surveillance and privacy violations which had become commonplace in the beginning of the twenty-first century.

See also

Espionage

Foldering

PirateBox

USB dead drop

References

Robert Wallace and H. Keith Melton, with Henry R. Schlesinger, Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA's Spytechs, from Communism to al-Qaeda, New York, Dutton, 2008. ISBN 0-525-94980-1. Pp. 43-44, 63, and 74-76.

Jack Barth, International Spy Museum Handbook of Practical Spying, Washington DC, National Geographic, 2004. ISBN 978-0-7922-6795-9. Pp. 119-125.

Wettering, Frederick L. (2001-07-01). "The Internet and the Spy Business". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 14 (3): 342–365. doi:10.1080/08850600152386846. ISSN 0885-0607. S2CID 153870872.

Nick Paton Walsh, The Guardian (23 January 2006). "Moscow names British 'spies' in NGO row". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

Bibliography

"Russians accuse 4 Britons of spying".International Herald Tribune. January 24, 2006. News report on Russian discovery of British "wireless dead drop".

"Old spying lives on in new ways". BBC. 23 January 2006.

Madrid suspects tied to e-mail ruse. International Herald Tribune. April 28, 2006.

Military secrets missing on Ministry of Defence computer files

Robert Burnson, "Accused Chinese spy pleads guilty in U.S. 'dead-drop' sting", Bloomberg, 25 novembre 2019[1].

Robert Wallace and H. Keith Melton, with Henry R. Schlesinger, Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA's Spytechs, from Communism to al-Qaeda, New York, Dutton, 2008. ISBN 0-525-94980-1.

The hidden history of the United States: https://thememoryhole.substack.com/

In the conclusive chapter of this revealing series, we delve deeper into the mechanisms of elite control within the economic framework. Discover the intricacies of how stock ownership and shared directorates create an interconnected web, particularly among ruling class banks and insurance companies, solidifying their dominance.

Explore a comprehensive assessment of wealth and income distribution in the nation, shedding light on the disparities that underscore the power dynamics. Unveil the role and significance of mass media within this structure, highlighting how elite-controlled media operate as a critical component of the system of control.

Delve into the nuanced examination of election control and gain insights from a review of "Trading with the Enemy." Witness a thought-provoking segment from "America/from Hitler to MX," exposing the paradoxical involvement of American economic institutions aiding Axis powers during World War II while the US was engaged in combat against them.

As the finale approaches, witness a concise exploration into actionable steps toward fostering genuine democracy within the United States. Join us in this thought-provoking conclusion as we ponder the pathways to a more equitable and democratic future.

The dark side of history: https://thememoryhole.substack.com/

Louis Patrick Gray III (July 18, 1916 – July 6, 2005) was acting director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from May 3, 1972, to April 27, 1973. During this time, the FBI was in charge of the initial investigation into the burglaries that sparked the Watergate scandal, which eventually led to the resignation of President Nixon. Gray was nominated as permanent Director by Nixon on February 15, 1973, but failed to win Senate confirmation.[3] He resigned as Acting FBI director on April 27, 1973, after he admitted to destroying documents that had come from convicted Watergate conspirator E. Howard Hunt's safe—documents received on June 28, 1972, 11 days after the Watergate burglary, and given to Gray by White House counsel John Dean.[4]

Gray remained publicly silent about the Watergate scandal for 32 years, speaking to the press only once, near the end of his life; this was shortly after Gray's direct subordinate at the FBI, FBI Deputy Director Mark Felt, revealed himself to have been the secret source to The Washington Post known as "Deep Throat".

Early life and education

Gray was born on July 18, 1916, in St. Louis, Missouri, the eldest son of Louis Patrick Gray Jr., a Texas railroad worker. He worked three jobs while attending schools in St. Louis and Houston, Texas, graduating from St. Thomas High School in 1932, at the age of 16 (having skipped two grades). Gray initially attended Rice University; however, his true goal was to be admitted to the United States Naval Academy. He was finally admitted to the Naval Academy in 1936 and he immediately dropped out of Rice University in his senior year so he could attend.

At the time, however, Gray could not afford the bus or train fare to Annapolis, so he hired on as an apprentice seaman on a tramp steamer out of Galveston. During the journey to Philadelphia (the closest the steamer could get him to Maryland), Gray taught calculus to the ship's captain, a Bulgarian named Frank Solis, in return for basic lessons in navigation. Once in Philadelphia, Gray hitchhiked to Annapolis.[5]

Once at the academy, Gray walked onto the football team as the starting quarterback, played varsity lacrosse and boxed as a light heavyweight. In 1940, Gray received a Bachelor of Science degree from the Naval Academy.

Naval career

The United States Navy commissioned Gray as a line officer, and he served through five submarine war patrols in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. He suffered a ruptured appendix at the start of his sixth patrol and was unable to get to a hospital for 17 days, an ordeal that should have killed him.[6] In 1945, Gray visited Beatrice Castle Kirk (1923–2019), the widow of his Naval Academy classmate, Lieutenant Commander Edward Emmet DeGarmo (1917–1945). They were married in 1946. He adopted her two sons, Alan and Ed; and they had two of their own, Patrick and Stephen.[6]

In 1949, Gray received a Juris Doctor degree from George Washington University Law School, where he edited the law review and became a member of the Order of the Coif. He was admitted to practice before the Washington, D.C., Bar in 1949; later, he was admitted to practice law by the Connecticut State Bar, the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, the United States courts of appeals, the United States Court of Claims, and the Supreme Court of the United States.[7]

By 1960, Gray's achievements in the Navy included commanding the U.S.S. Tiru (SS-416) and two other submarines on war patrols during the Korean War; earning the rank of captain two years before he was legally allowed to be paid for it; and serving as congressional liaison officer for the United States Secretary of Defense, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Chief of Naval Operations. He indicated his desire to retire from the Navy, but Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh Burke told him, "If you stay, you'll have my job some day."[6] He did not stay, but joined a Connecticut law firm in 1961.

Department of Justice

In 1969, Gray returned to the federal government and worked under the Nixon administration in several different positions. In 1970, President Nixon appointed him as Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Division in the Department of Justice. In 1972, Gray was nominated to be Deputy Attorney General, but before he could be confirmed by the full United States Senate his nomination was withdrawn.

Acting Director of FBI

Instead, President Nixon designated him as Acting Director of the FBI after the death of J. Edgar Hoover. Gray served for less than a year. Day-to-day operational command of the Bureau remained with Associate Director Mark Felt.

Watergate involvement

Watergate scandal

The Watergate complex in 2006

Events

List

People

Watergate burglars

Groups

CRP

White House

Judiciary

Journalists

Intelligence community

Mark Felt ("Deep Throat") L. Patrick Gray Richard Helms James R. Schlesinger

Congress

Related

vte

Watergate and the FBI's investigation

On June 17, 1972, just six weeks after Gray took office at the FBI, five men were arrested after breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate hotel complex in Washington, D.C.

Gray first learned of the Watergate break-ins on June 17 from Wes Grapp, the Special Agent in Charge of the Los Angeles field office. Gray immediately called Mark Felt, his second in command. At the time, Felt only had limited information, remaining unclear as to whether it was a burglary or bombing attempt.[8]

Felt had more information the next day, when he informed Gray that the burglars had connections to the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), that one burglar (McCord) was head of security for the committee, and that at least one listening device had been found. Gray recalled the conversation concluding with the exchange:

"Are you absolutely certain that we have jurisdiction?" I asked.

"I'm sure of it," he [Felt] answered.

"Just check it and be absolutely certain," I ordered. "And then investigate it to the hilt with no holds barred."[9]

On the same day, June 18, 1972, Gray also met later-identified Watergate conspirator Fred LaRue in California. The two discussed Watergate, according to LaRue, and made arrangements to meet again back in Washington, D.C.[10] In his own memoir, Gray relates the LaRue meeting as a chance encounter at a hotel swimming pool and quotes their entire Watergate-related conversation:

"The Watergate thing is a hell of a thing," he said.

"You bet it is, Fred," I answered. "We're going to investigate the hell out of it."

That was all either of us said about it.[11]

For the first six months of the investigation, Gray remained heavily involved. It was only when it became apparent that the White House was involved that Gray recused himself from the investigation and handed control over to Mark Felt.[12]

Cover-up

On June 23, 1972, White House Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman and President Nixon held one of the infamous "smoking gun" conversations in which they conspired to use the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to block the FBI investigation into the money trail leading from the Watergate burglars to the Committee to Re-elect the President, which would constitute hard evidence that Committee members were involved in the planning of the burglaries.

According to Gray, this plan was first put into action when he had a meeting with Vernon Walters, then deputy director of the CIA, in which he quotes Walters as falsely saying, "If the investigation gets pushed further south of the border… it could trespass onto some of our covert projects. Since you've got these five men under arrest, it will be best to taper the matter off here." This conversation implicitly stated that the FBI should not interview Manuel Ogarrio and Kenneth Dahlberg, individuals connected with the money used to fund the Watergate burglars.[13]

This would later be backed up by the Director of the CIA, Richard Helms, when he specifically told Gray that Karl Wagner and John Caswell should also not be interviewed, as they were, he stated, active CIA agents at the time.[14]

The basis for such a request came from a long-standing understanding between the CIA and the FBI that they would not reveal each other's informants. This effort by the White House and the CIA succeeded in delaying the interviews of both Ogarrio and Dahlberg for a little more than one week, at which point Gray and his senior FBI staff, including Mark Felt, Charlie Bates, and Bob Kunkel, decided that, due to the increasing importance of these individuals in the investigation, they needed a written request from the CIA not to interview them, which would have to state in greater detail the reasons for not interviewing these individuals. Once the decision was made, Gray called Vernon Walters and demanded that written request the next morning, or he would order the interviews to go forth.[15]

The next morning, Vernon Walters arrived and delivered a three-page memorandum, marked "SECRET", that did not ask the FBI to hold off on the interviews. The meeting concluded with Walters suggesting to Gray that he should warn the President that some members of the White House staff were hindering the FBI's investigation. After the conversation, Gray ordered the interviews to proceed immediately.[16]

Ultimately, the CIA cover-up delayed the FBI investigation no more than two weeks.

While not active in any Watergate activities per se, Gray was aware through his dealings with John Dean that the White House was concerned about what might be discovered from a full-field FBI investigation and explored what he could do to limit the investigation or shift it away from the Bureau's jurisdiction.[17] As Dean wrote in his Watergate memoir "Blind Ambition," he used Gray as a shill knowing that "we could count on Pat Gray to keep the Hunt material from becoming public, and he did not disappoint us."[18] In fact, even though he thought of this as a political not criminal situation and that he was ultimately serving the President as the "nation's chief law enforcement officer," Gray would come dangerously close to collusion because he chose to be useful to the White House without asking the hard questions. Dean goes on to say, "I met Pat Gray secretly at his home in southwest Washington. We were both apprehensive about the meeting as we walked to a park and sat down on a bench overlooking the Potomac, discussing my request to obtain FBI 302s and AirTels on the Watergate investigation."[18]

Felt and the search for the source

The Nixon White House tapes reveal that Bob Haldeman told Nixon that Felt was the source of leaks of confidential information contained in the FBI's investigation to various members of the press, including Bob Woodward of The Washington Post. Gray claimed that he resisted five separate demands from the White House to fire Felt, stating that he believed Felt's assurances that he was not the source. Eventually, Gray demanded to know who was claiming Felt to be leaking. Attorney general Richard Kleindienst told Gray that Roswell Gilpatric, former deputy secretary of defense under John F. Kennedy and now outside general counsel to Time, had told John Mitchell that Felt was leaking to Sandy Smith of Time magazine.[19][20]

After Felt admitted in the May 2005 Vanity Fair article that he lied to Gray about leaking to the press, Gray claimed that Felt's bitterness at being passed over was the cause of his decision to leak to Time, The Washington Post, and others.[21]

Confirmation hearings

In 1973, Gray was nominated as Hoover's permanent successor as head of the FBI. This action by President Nixon confounded many, coming at a time when revelations of involvement by Nixon administration officials in the Watergate scandal were coming to the forefront. Under Gray's direction, the FBI had been accused of mishandling the investigation into the break-in, doing a cursory job and refusing to investigate the possible involvement of administration officials. Gray's Senate confirmation hearing was to become the Senate's first opportunity to ask pertinent questions about the Watergate investigation.

During the confirmation hearing, Gray defended his bureau's investigation. During questioning, he volunteered that he had provided copies of some of the files on the investigation to White House Counsel John Dean, who had told Gray he was conducting an investigation for the President.[22] Gray testified that before turning over the files to Dean, he had been advised by the FBI's own legal counsel that he was required by law to comply with Dean's order. He confirmed that the FBI investigation supported claims made by The Washington Post and other sources, about dirty tricks committed and funded by the Committee to Re-Elect the President, and in particular, activities of questionable legality committed by Donald Segretti. The White House had for months steadfastly denied any involvement in such activities.

During the hearings, Gray testified that Dean had "probably lied" to the FBI,[23] increasing the suspicions of many of a cover-up. The Nixon administration was so angered by this statement that John Ehrlichman told John Dean that Gray should be left to "twist slowly, slowly in the wind."

Destruction of documents and resignation from the FBI

On June 21, 1972, Gray met with John Dean and John Ehrlichman in Ehrlichman's office. During this meeting, Gray was handed several envelopes full of documents from the personal safe of E. Howard Hunt. Dean instructed Gray, in the presence of John Ehrlichman, that the documents were "national security documents. These should never see the light of day."[24] Dean further repeatedly told Gray that the documents were not Watergate-related.

Six months later, Gray said he finally looked at the papers as he burned them in a Connecticut fireplace. "The first set of papers in there were false top-secret cables indicating that the Kennedy administration had much to do with the assassination of the Vietnamese president (Diem)," Gray said. "The second set of papers in there were letters purportedly written by Senator Kennedy involving some of his peccadilloes, if you will."[4]

After learning from Ehrlichman that John Dean was cooperating with the U.S. attorney and would be revealing to him what happened on June 21, Gray told his staunchest congressional supporter, Senator Lowell Weicker, so that he might be prepared for that revelation. As a result, Senator Weicker leaked this revelation to some chosen reporters.[25]

Following this revelation, Gray was forced to resign from the FBI on April 27, 1973.[26]

Legal struggles

For the next eight years, Gray defended his actions as Acting Director of the FBI, testifying before five federal grand juries and four committees of Congress.[27]

On October 7, 1975, the Watergate Special Prosecutor informed Gray that the last Watergate-related investigation of him had been formally closed.[28] Gray was never indicted in relation to Watergate, but the scandal dogged him afterwards.

In 1978, Gray was indicted, along with Assistant Director Edward Miller, for allegedly having approved illegal break-ins during the Nixon administration. Gray vehemently denied the charges, which were dropped in 1980. Felt and Miller, who had approved the illegal break-ins during the tenures of four separate FBI directors, including Hoover, Gray, William Ruckelshaus, and Clarence M. Kelley, were convicted and later pardoned by President Ronald Reagan. Exonerated by the Department of Justice after a two-year investigation,[29][30][31] Gray returned to his law practice in Connecticut.

Later life

After his time in Washington, Gray returned to practicing law at the firm of Suisman, Shapiro, Wool, Brennan, Gray & Greenberg (SSWBGG) in New London, Connecticut.[32]

In a 2005 Vanity Fair article,[33] Deputy Director Mark Felt claimed to be Deep Throat, the infamous source of leaks to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.[34] Woodward, Bernstein, and Post executive editor Benjamin C. Bradlee confirmed the claim.[35][36] Gray spoke about the Watergate scandal for the first time in 32 years on June 26, 2005, ten days before his death from pancreatic cancer. He told ABC's This Week that he was in "total shock, total disbelief" when asked about Felt's claim. "It was like I was hit with a tremendous sledgehammer."[37]

Gray died on July 6, 2005.[38] He was working on his memoirs with his stepson Edward Gray, using his extensive and never-released personal Watergate files. His stepson finished the book In Nixon's Web: A Year in the Crosshairs of Watergate,[39] which disputes the claim that Felt was Deep Throat, citing Woodward's own notes and other evidence as proof that Deep Throat was a fictional composite made up of several Woodward sources, only one of whom was Felt.[40]

Gray and the New York Times

In 2009, Bob Phelps, a former editor of The New York Times, and Robert M. Smith, a former reporter for the Times, claimed that they had received information from Gray that would have allowed the Times to break the Watergate story before The Washington Post, but they failed to act upon it.[41]

In August 1972, Gray and Smith had lunch. According to Smith, during this lunch Gray mentioned details of Donald Segretti and John Mitchell's involvement in the Watergate burglaries. Smith quotes Gray:

"[Gray] told me about a guy who burned his palm, and about Donald Segretti (by name).

And when he intimated over the entrée that the wrongdoing went further, I leaned back against the wall on my inside banquette and looked at him in frank astonishment.

"The attorney general?" I asked.

He nodded.

I paused.

"The president?" I asked.

He looked me in the eye without denial—or any comment. In other words, confirmation.[42]

After the lunch, Smith reportedly rushed to his editor, Phelps, with the story, but it amounted to nothing. Smith left his job the next day for Yale Law School, and Phelps lost track of the story while covering the 1972 Republican Convention.

However, while only Gray and Smith knew exactly what was said at that lunch, Gray's son, Edward, denies that his father could have implicated either the Attorney General or the President, stating:

The truth is that at the time of this luncheon—as my father testified multiple times under oath—neither he nor anyone else in the FBI had any evidence whatsoever that the president was involved.[43]

Gray goes on to point out that at the time of this lunch the Attorney General was Richard Kleindienst, who was never implicated in any of the Watergate scandals. Even if Smith meant that he was talking about John Mitchell, the former Attorney General, Gray further points out that no one (outside of the conspirators) knew of Mitchell's involvement until the following April, when John Dean admitted as much to special prosecutors.[43]

Documents

Gray was a meticulous record-keeper, which is most easily evidenced by the 40 boxes of personal records he took with him from his year with the FBI.[44] The archive would grow even after Gray left the FBI as a direct result of the legal proceedings in which he was forced to take part in the years to follow.

This archive has become what is undoubtedly the "most complete set of Watergate investigative records outside the government."[45]

Selected Navy awards

American Defense Service Medal

American Campaign Medal

Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medal

World War II Victory Medal

National Defense Service Medal

Korean Service Medal

United Nations Korea Medal

See also

World War II portalBiography portal

Helen Gandy

Notes

Kessler, Ronald (2003). The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. Macmillan. p. 29. ISBN 0-312-98977-6.

Gray, L. Patrick (March 3, 2009). In Nixon's Web: A Year in the Crosshairs of Watergate. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0805089189. "He [L. Patrick Gray III] was a lifelong Republican, but Richard Nixon considered him a threat"

NYT1 1973

Page 3 of 3 (June 26, 2005). "Page 3: 'Deep Throat's' Ex-Boss Shocked by Revelation - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. xix–xx

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. xx

FBI 2008

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 59

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 60

Emery 1995, p. 157

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. 60–61

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 65

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 72

USG 1974, p. 463

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. 85–87

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. 88–89

Haldeman, H.R., The Haldeman Diaries, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1994, 474-75.

Dean, John, Blind Ambition, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976, 122.

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 133

The claim by Gray that Roswell Gilpatric had informed John Mitchell about Felt being the leaker was called "far-fetched" by the deceased Gilpatric's son, John. John Gilpatric told The New York Times that his father never mentioned knowing John Mitchell. However, a tape in the Oval Office has Nixon telling Gray that the source for this accusation was "a lawyer... for Time." For more on this question, see Roswell Gilpatric

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 280

Sussman 1974, pp. 165–166

Sussman 1974, p. 173

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. 81–82

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. 238–243

Sullivan, Patricia. "Watergate-Era FBI Chief L. Patrick Gray III Dies at 88", Washington Post (July 7, 2005): "Mr. Gray, a Nixon loyalist often described as a political naif, finally was forced to resign April 27, 1973...."

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. xxi

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 267

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. 265–267

CHTribune 1980

UPI (December 30, 1980). "Exonerated Gray says he'll sue government". The Bulletin. Retrieved March 31, 2010.[permanent dead link]

Purdum, Todd S. (July 7, 2005). "L. Patrick Gray III, Who Led the F.B.I. During Watergate, Dies at 88". The New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

O'Connor 2005

"W. Mark Felt Reveals Himself as Deep Throat, Ends Years of Post-Watergate Speculation". Vanity Fair. October 17, 2006.

Woodward, Bob. The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate's Deep Throat, Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0-7432-8715-0

"The Watergate Story | Deep Throat Revealed - The Washington Post". The Washington Post.

NYT3 2005, p. B4

HIGH 2008

Stout, David (March 9, 2008). "Ex-F.B.I. Chief's Book Revisits Watergate". The New York Times.

Gray III & Gray 2008, pp. 289–302

NYT4 2009

AJRSmith 2009

AJRGray 2009

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 303

Gray III & Gray 2008, p. 304

References

Biographical entry, St. Thomas High School Hall of Honor, archived from the original on May 12, 2008, retrieved July 2, 2008

Emery, Fred (1995), Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-684-81323-8

Directors, Then and Now, The Federal Bureau of Investigation, archived from the original on August 13, 2008, retrieved August 7, 2008

Gray III, L. Patrick; Gray, Ed (2008), In Nixon's Web: A Year in the Crosshairs of Watergate, Times Books/Henry Holt, ISBN 978-0-8050-8256-2

O'Connor, John D. (July 2005), "I'm the Guy They Called Deep Throat", Vanity Fair, retrieved July 2, 2008

Simeone, John; Jacobs, David (2003), Complete Idiot's Guide to the FBI, Alpha Books (published 2002), ISBN 0-02-864400-X

Theoharis, Athan G. (2000), The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide, New York: Checkmark Books, ISBN 0-8160-4228-4

Woodward, Bob (2005), The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate's Deep Throat, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-7432-8715-0

Sussman, Barry (1974), The Great Cover-up: Nixon and the Scandal of Watergate, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, ISBN 0-690-00729-9

United States Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary (1974), Statement of information : hearings before the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Ninety-third Congress, second session, pursuant to H. Res. 803, a resolution authorizing and directing the Committee on the Judiciary to investigate whether sufficient grounds exist for the House of Representatives to exercise its constitutional power to impeach Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States of America. May–June 1974 (Book II), U.S. Government Printing Office

Johnston, David (June 27, 2005), "Ex-F.B.I. Chief Calls Deep Throat's Unmasking a Shock", New York Times, retrieved March 21, 2009

Rugaber, Walter (April 28, 1973), "A Sudden Decision: Chief Resigns After Citing Reports He Destroyed Files", New York Times, retrieved March 21, 2009

Crewdson, John (April 6, 1973), "Nixon Withdraws Gray Nomination as F.B.I. Director", New York Times, retrieved March 21, 2009

Perez-Pena, Richard (May 24, 2009), "2 Ex-Timesmen Say They Had a Tip on Watergate First", New York Times, retrieved May 31, 2009

Smith, Robert (May 26, 2009), "Before Deep Throat", American Journalism Review, retrieved June 1, 2009

Gray, Edward (May 28, 2009), "Taking Issue", American Journalism Review, retrieved June 1, 2009

"Court Clears ex-FBI Chief", The Chicago Tribune, December 12, 1980

External links

Louis Patrick Gray, III, www.fbi.gov.

L. Patrick Gray, Deep Throat's Boss at F.B.I., Dies at 88. New York Times, July 6, 2005.

Ex-F.B.I. Chief Calls Deep Throat's Unmasking a Shock. New York Times, June 27, 2005.

'Deep Throat's' Ex-Boss Shocked by Revelation. ABC News This Week, June 26, 2005.

Obituary. Seattle Times, July 7, 2005.

White House Tapes relating to FBI. National Security Archives, July 2, 2008.

Biographical entry. St. Thomas High School Hall of Honor, July 2, 2008.

Ed Gray on "Morning Joe." MSNBC, March 7, 2008.

Ex-F.B.I. Chief's Book Revisits Watergate New York Times, March 9, 2008.

In Nixon's Web: Watergate and the FBI

Gray in Black and White Archived June 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The American Spectator, June 2008.

Government offices

Preceded by

J. Edgar Hoover

Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Acting

1972–1973 Succeeded by

William Ruckelshaus

Acting

vte

Directors of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Bureau of Investigation

Finch Bielaski Allen Flynn Burns Hoover

Federal Bureau

of Investigation

Hoover Gray Ruckelshaus Kelley Adams Webster Otto Sessions Clarke Freeh Pickard Mueller Comey McCabe Wray

Italics denotes an Acting Director.

Authority control databases Edit this at Wikidata

International

FAST ISNI VIAF

National

Germany United States

Other

NARA SNAC

Categories:

1916 births2005 deathsUnited States Navy personnel of the Korean WarUnited States Navy personnel of World War IIConnecticut lawyersDeaths from cancer in FloridaDeaths from pancreatic cancerDirectors of the Federal Bureau of InvestigationGeorge Washington University Law School alumniLawyers from St. LouisMilitary personnel from St. LouisNixon administration personnel involved in the Watergate scandalRice University alumniSt. Thomas High School (Houston, Texas) alumniUnited States Assistant Attorneys General for the Civil DivisionUnited States Naval Academy alumniUnited States Navy officers

John O'Beirne Ranelagh is a television executive and producer, and an author of history and of current politics. He was created a Knight First Class by King Harald V of Norway in 2013 in the Royal Norwegian Order of Merit, for outstanding service in the interest of Norway.

Ranelagh was born in New York and moved to rural Ireland following his parents’ 1946 marriage.[1]

Education

He read Modern History at Christ Church, Oxford, and went on to take a Ph.D. at Eliot College, University of Kent.

Career

He was Campaign Director for "Outset", a charity for the single homeless person, where he pioneered the concept of charity auctions. From 1974 to 1979 he was at the Conservative Research Department where he first had responsibility for Education policy, and then for Foreign policy. He started his career in television with the British Broadcasting Corporation, first for BBC News and Current Affairs on Midweek. As Associate Producer he was a key member of the BBC/RTE Ireland: A Television History 13-part documentary series (1981). Later a member of the team that started Channel 4, he conceived the Equinox program,[2] developed the "commissioning system", and served as Board Secretary. He was the first television professional appointed to the Independent Television Commission (ITC), a government agency which licensed and regulated commercial television in Britain from 1991 to 2003.[3]

Eventually Ranelagh relocated to Scandinavia where he continued in television broadcasting.[4] There he has been with various companies: as Executive Chairman for NordicWorld; as Director for Kanal 2 Estonia; and, as Deputy Chief Executive and Director of Programmes for TV2 Denmark. Later Ranelagh worked at TV2 Norway as Director of Acquisition, and at Vizrt as deputy Chairman and then Chairman .[5]

Ranelagh stood as the Conservative Party candidate in Caerphilly in the 1979 general election. He stood for the seat of Bethnal Green and Bow in the 1977 Greater London Council election.[6]

Books

Ranelagh has also written several books:[7]

"The I.R.B. from the Treaty to 1924," in Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 20, No. 77 (March 1976).

"Science and Education," CRD, 1977.

"Human Rights and Foreign Policy," with Richard Luce, CPC, 1978.

Ireland. An illustrated history (Oxford University 1981);

A Short History of Ireland (Cambridge University 1983, 2d ed. 1995, 3d ed. 2012);

The Agency. The rise and decline of the CIA (New York: Simon and Schuster 1986, pb. ed. 1987);

"Secrets, Supervision and Information," in Freedom of Information; Freedom of the Individual, ed. Julia Neuberger, 1987.

"The Irish Republican Brotherhood in the revolutionary period, 1879–1923," in The Revolution in Ireland, 1879–1923, ed. D.G. Boyce, 1988.

Den Anden Kanal, Tiderne Skifter, 1989.

Thatcher's People. An insider's account of the politics, the power and the personalities (HarperCollins 1991);

CIA: A History (London: BBC Books, illustrated edition 1992).

Encyclopædia Britannica, "Ireland," 1993–

"Through the Looking Glass: A comparison of United States and United Kingdom Intelligence cultures," in In the Name of Intelligence, eds. Hayden B. Peake and Samuel Halpern, 1998.

"Channel 4: A view from within," in The making of Channel 4, ed. Peter Catterall, 1998.

Family

John Ranelagh's Irish father was James O'Beirne Ranelagh (died 1979 Cambridge) who had been in the IRA in 1916 and later, fighting on the Republican side in the 1922–24 Civil War. His mother was Elaine (née Lambert Lewis). She had been a young American folklorist with her own WNYC radio program,[8] and thereafter became the noted author, E. L. Ranelagh (born 1914 New York, died 1996 London).[9] A native New Yorker, she had moved to rural Ireland following her 1946 marriage to James. Their son John Ranelagh, who has three younger sisters, Bawn, Elizabeth and Fionn, was born in 1947.[10] His wife is Elizabeth Grenville Hawthorne, author of Managing Grass for Horses (2005). Hawthorne is the daughter of the late Sir William Hawthorne.

See also

Channel 4

Equinox

TV2 Norway

Notes

"The Irish Republican Brotherhood 1914 – 1924". Irish Academic Press. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

Equinox ran from 1986 to 2001 and presented science features and documentaries.

Speaker Bio John Ranelagh at natpe.2014 Archived 2011-05-15 at the Wayback Machine.

Video Snack with John Ranelagh, TV2 Norway.

Speaker Bio John Ranelagh at natpe.2014 Archived 2011-05-15 at the Wayback Machine.

"Greater London Council Election" (PDF). 5 May 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

His The Agency (1986), won the National Intelligence Book Prize, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. In 2000 the Washington Post listed it as one if the ten best books on Intelligence in the twentieth century. To the present day it is recommended reading for students of Intelligence. He is also the author of two books on the history of Ireland, one of which – "A Short History of Ireland" – has been in constant print since 1983.Amazon's John Ranelagh page

Broadcasting from New York City, her show featured folk songs. In the late 1930s she helped introduce the blues of Huddie Ledbetter to radio audiences.

Among the books of E. L. Ranelagh: Himself and I (New York: Citadel 1957), under the pen-name Anne O'Neill-Barna; The Past We Share. The near eastern ancestry of western folk literature (London: Quartet 1979); Men on Women (London: Quartet 1985), a history of gender relations. Later, she also published paperbacks on "Rugby Jokes".

Obituaries: Elaine O'Beirne-Ranelagh

External links

Exclusive Interview with John O'Beirne Ranelagh

Video Snack with John Ranelagh, TV2 Norway